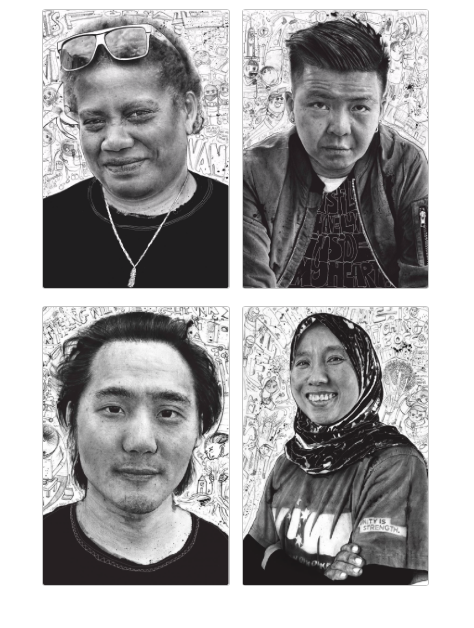

For The Monthly, André Dao, Sherry Huang and I wrote about the Chinese workers at the centre of a dispute at the Midfield abattoir in Warrnambool. It begins like this:

In May 2016, Jack Zhao posted to a private Facebook page to advertise for meatworkers at Midfield Meat International, an abattoir in Warrnambool on Victoria’s southwest coast. “Today,” he wrote in Mandarin, “is an important day. I am happy to announce that we are about to expand our business. Ten years ago, the first group of Chinese 457 visa holders arrived at Midfield and boosted our revenue up to ten times! We became one of the top 50 private corporations in the country. Today, another 50 Chinese 457 visa holders arrived at Midfield.”

Though Jack Zhao wrote of “we” and “our”, he was not actually employed by Midfield. Instead, he was a labour hire contractor, tasked with recruiting workers from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan for Australian abattoirs. But without any Mandarin-speaking supervisors, the company effectively relied on Zhao and other labour hirers to manage its foreign workforce. Zhao’s Facebook post outlined what the latest round of recruits could expect: “Good 457 workers will get your PR status, you will have five things in your hand: wife, kids, house, money, car! As long as you are a hard worker, here is your great opportunity.”

Naturally, such an opportunity doesn’t come cheap. Some of these new migrant-worker recruits had paid a Chinese broker up to $70,000 to have a shot at “PR”, shorthand for a visa with permanent residency: the 186 visa allows the holder to live in Australia indefinitely, with work and study rights, access to Medicare, the ability to sponsor relatives, and a pathway to Australian citizenship. This, then, was the bargain: find the money or borrow it against your future wages and work for a single abattoir for at least three years on a temporary 457 visa, with limited rights, and, in return, you would get the promise of a ticket to the lucky country.

Facilitating these opportunities is a big business. Zhao’s boss was Zu Neng “Scott” Shi, the director of a network of dozens of labour hire companies providing foreign workers to at least 42 abattoirs around Australia. Between 2008 and 2017 his syndicate generated $349 million in revenue from meatworker recruitment. There was also money to be made exporting the meat. Shi appeared on the Chinese government–owned China Central Television as the “beef boss”, touting his access to high-quality Australian meat for import. The business is opaque: in 2018, the Australian Tax Office accused Shi and his companies of phoenixing – the practice of liquidating a company once it gets into trouble, only to incorporate it again under a new name – and of owing $163 million in unpaid taxes. An industry insider explains the trade like this: “It’s all to do with blood, muscle and bone. It just happens that some is alive and some is dead.”

Read more at The Monthly.